What is it? A minimalist puzzle-adventurer about mental health.

Expect to pay $3.89/£2.89

Developer Rusty Lake

Publisher Second Maze

Reviewed on i7 9700K, RTX 2080 TI, 16GB RAM

Multiplayer? No

Link Official site

One of the most profound effects of a monochrome palette is to make you notice what isn’t there. There’s a tacit implication that something’s thematically, not just visually, missing when you watch a world in black and white. We tend to look at monochrome game worlds as a stylistic shorthand for grief, loss, depression, and other subject matter that can really fuck up your Sunday.

That’s certainly true of Rusty Lake’s The White Door, but in this point-and-click-meets ayahuasca journey you’re asking the question literally, not just figuratively: what’s missing? Small changes to the daily routine imposed by the white coats behind the white door; an empty white plate instead of the meals you’re used to receiving at exactly 5pm—these feel like major narrative revelations in the minimalist confines of your cell.

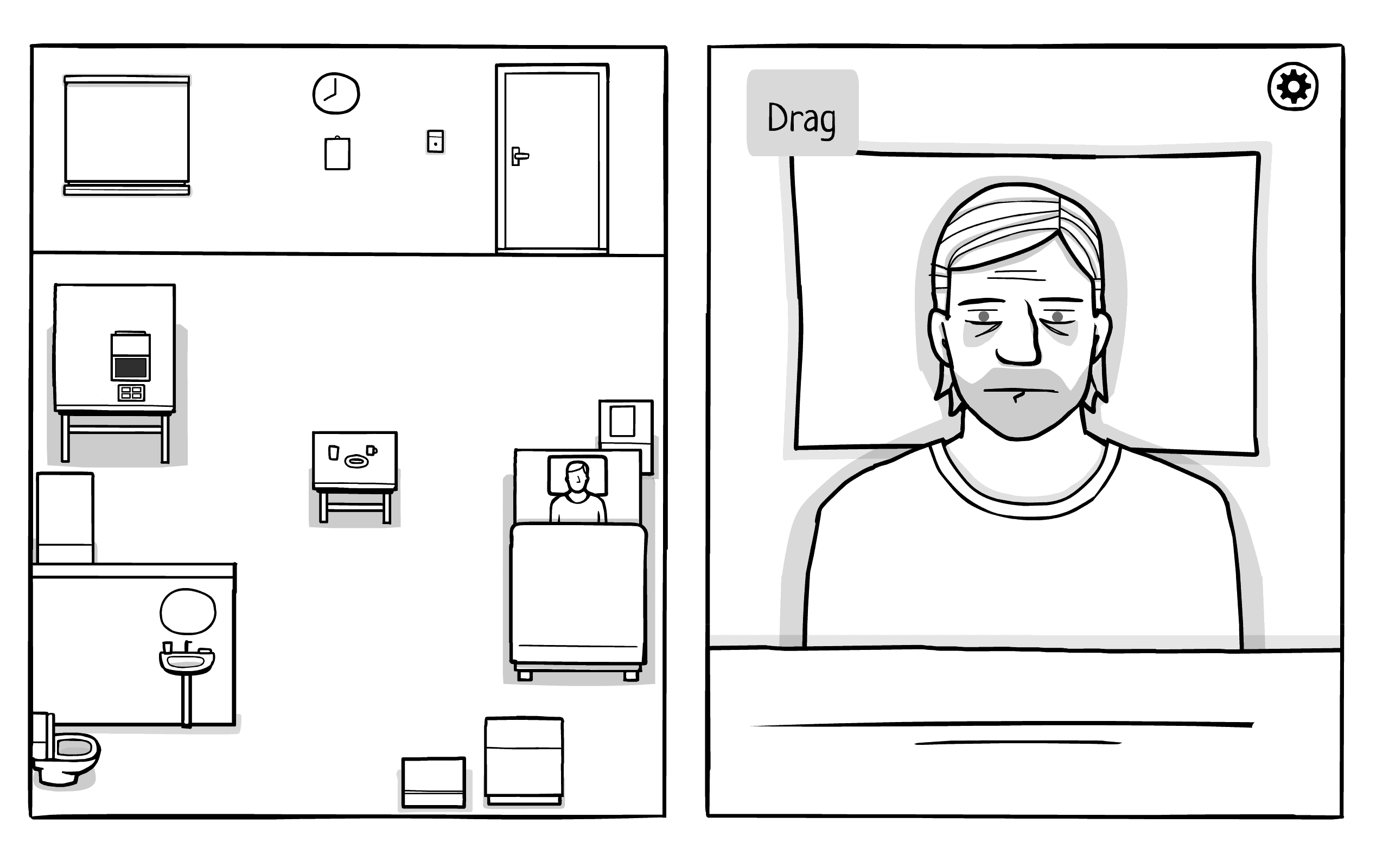

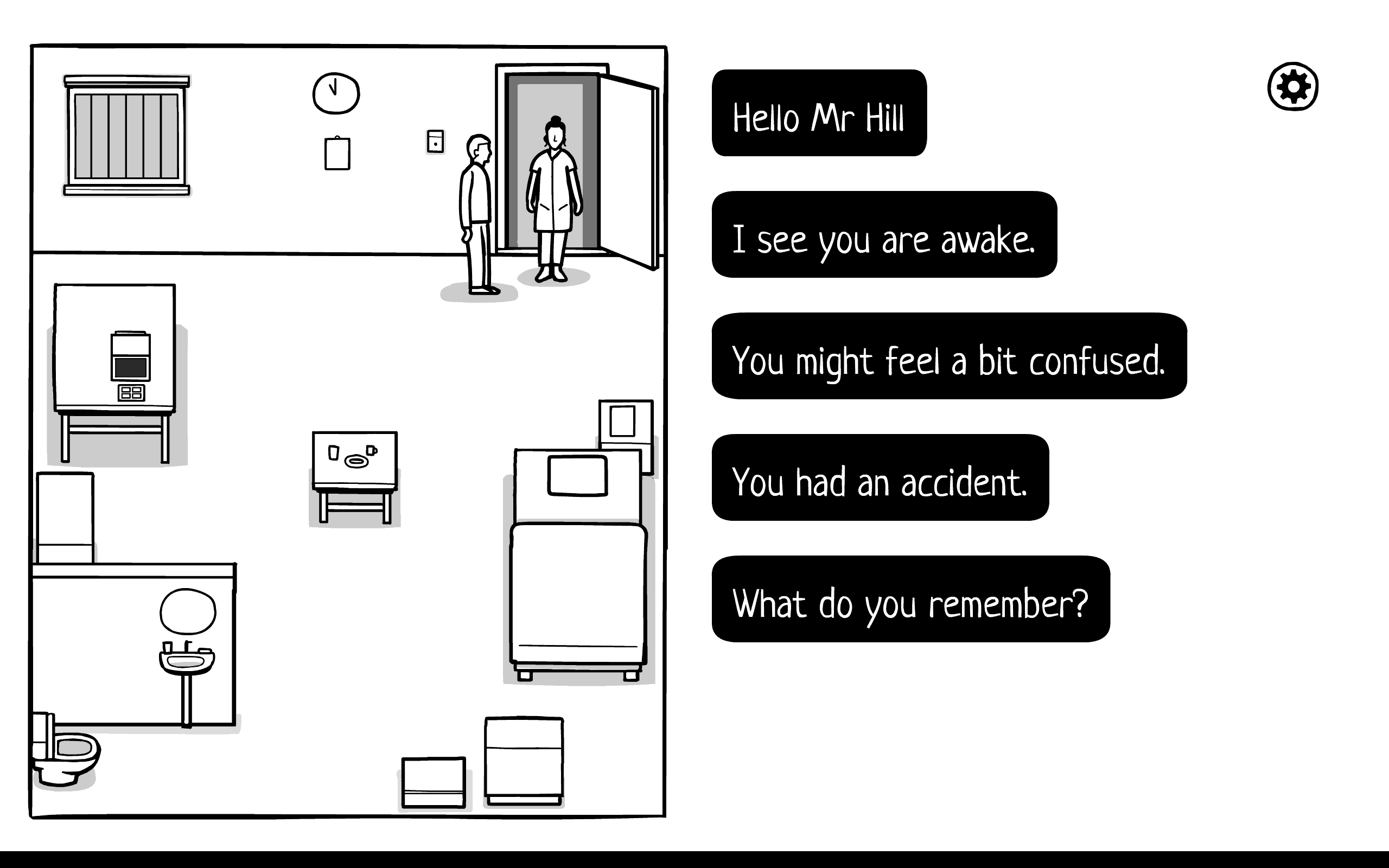

You are Robert Hill and the year is 1972. You know this because it’s written on the calendar on your wall and the driving license in your drawer. Otherwise, the wheres and whys of your life—most pertinently how you ended up in a mental health facility—elude both character and player. What follows is a few days of mundane hour-by-hour routine laid out by unseen people who, you hope, are caring for you.

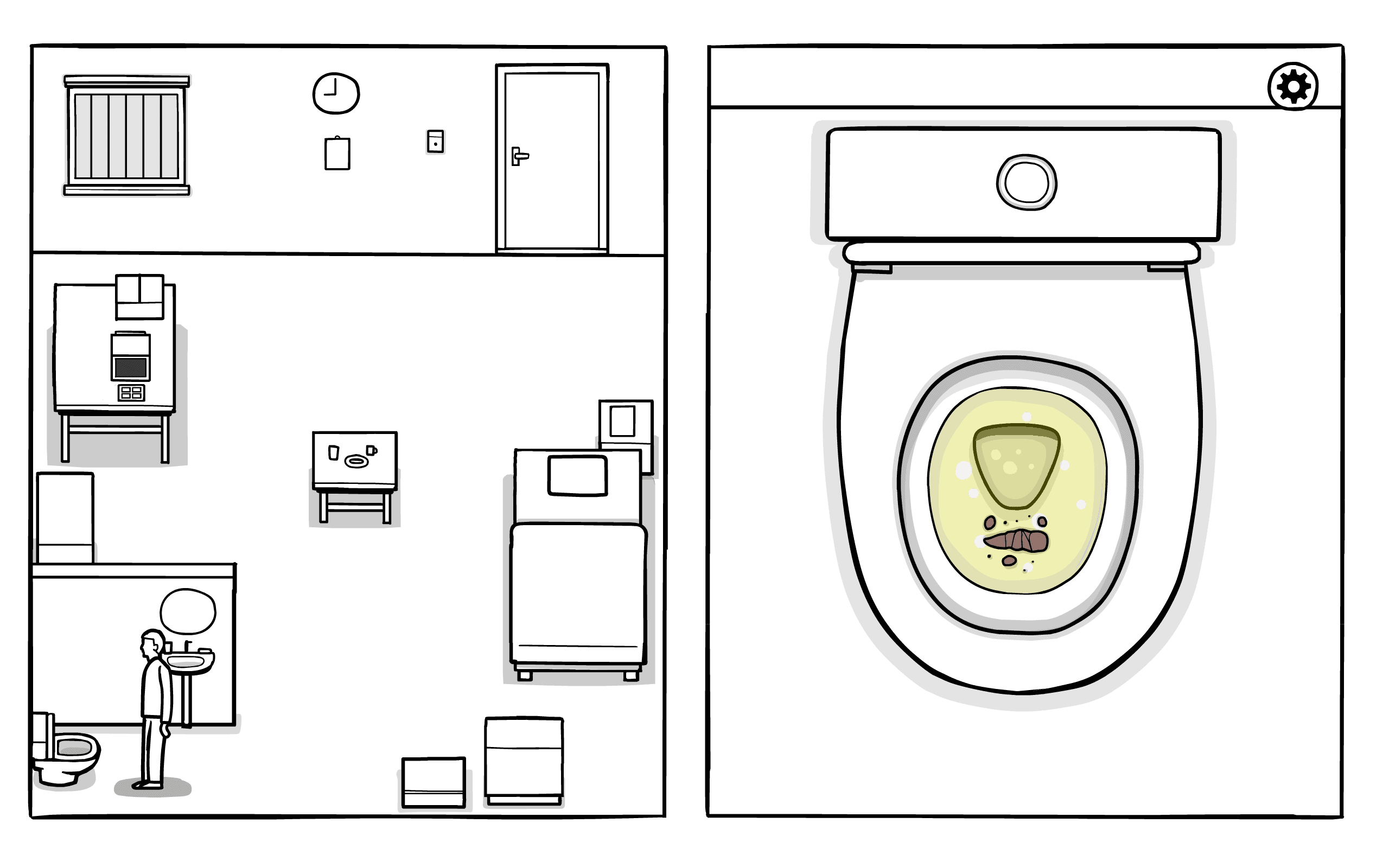

It’s a classic bout of testing the player’s obedience, pushing you further and further with prosaic tasks like brushing your teeth at the same time, every single morning, until you start to question things—to pick at the corners of that simple white box you’re confined within, and uncover something more complex.

This device works especially well in games because we’re so well-trained to suspend our disbelief—to forget that we’re following game designer’s script and just knuckle down with the task at hand. The fact it’s been employed so well elsewhere though lessens the impact here. When the lines of code start to infect the erstwhile cheery arcade game in Pony Island, corrupting the kid-friendly images with satanic symbols, or when Portal 2’s pristeen test chambers start to show the faintest signs of life outside the walls, my mind was blown. Years later in The White Door, when rats and shadowy figures invade your sterile room—figments of Robert’s troubled mind—I say to myself, ‘Yep, that old trick.’

While you poke about at the bits between the game, Robert too goes somewhere else between his monotonous days, escaping in his dreams. Here a story starts to form of how he might have ended up behind the eponymous door and why he looks so glum in the mirror every day.

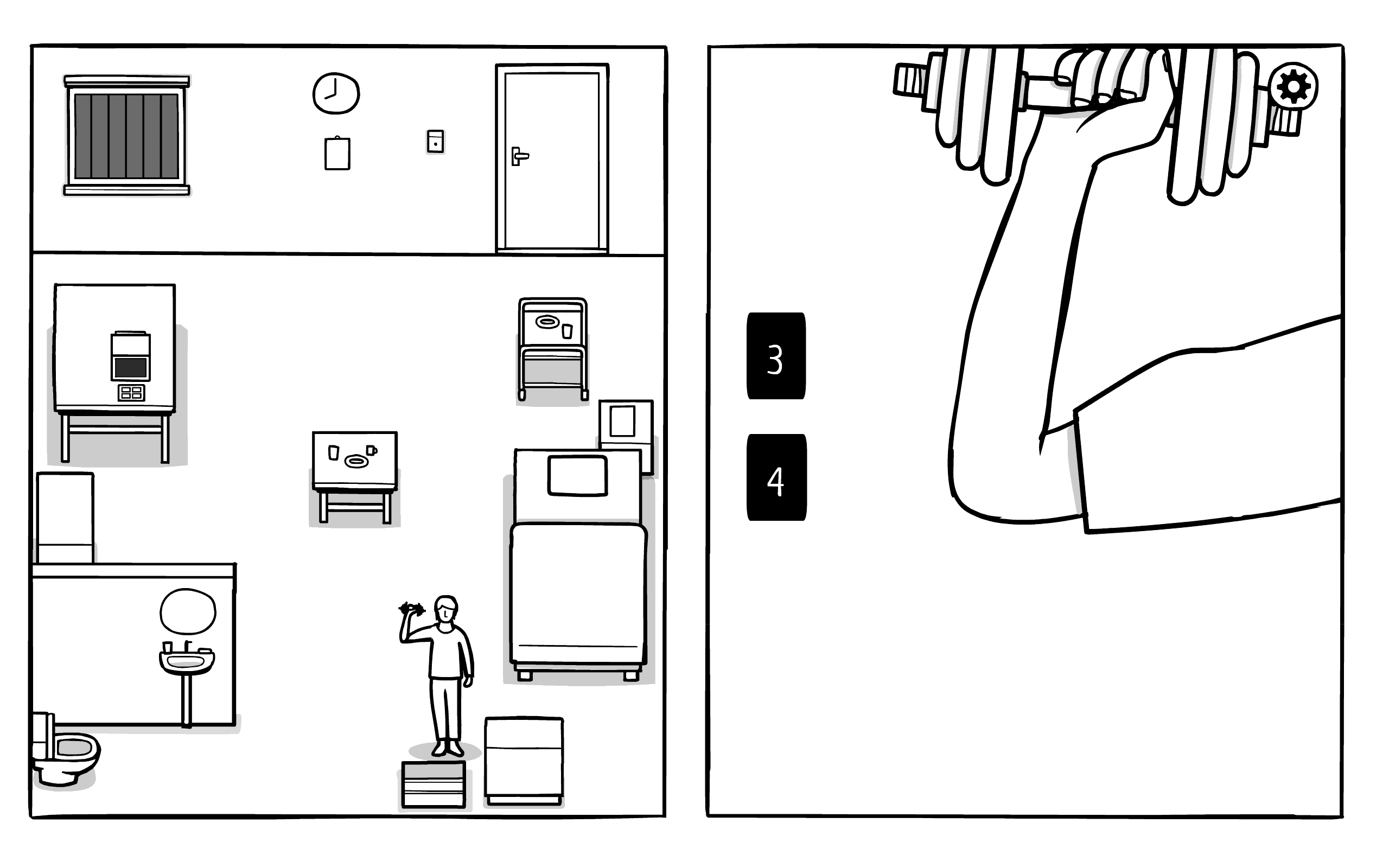

Mechanically it’s always light-touch. You might be dragging a coffee cup up to Robert’s lips as he narrates that he took another sip of coffee in a dream sequence, or answering multiple choice questions during your daily psychological examination. As it progresses it becomes something more like a traditional puzzle game, employing pattern recognition and logic challenges to gate progression, but The White Door’s woozy, reality-bending tone means you’re never sure of the rules.

Sometimes that’s a good thing. It means you don’t question why doing X produces outcome Y but instead just lose yourself to the flow of the journey. And in much the same way as the magical realism of Kentucky Route Zero led to tuning radios for no discernible reason, sometimes playing with the image you’re presented with and challenging your assumptions about it hold the key to moving forward.

You don’t question why doing X produces outcome Y but instead just lose yourself to the flow of the journey.

Note I said ‘sometimes’. Point-and-clicks have run the risk of being obtuse in their puzzle logic since Ron Gilbert still got IDed buying beers, so when you introduce the conceit that you’re a confused and amnesiac man being held in a room by people whose motives are unclear, well, the puzzles are going to get pretty messy, aren’t they? Logical they most certainly are not, and a few are just a bit too abstract to feel satisfying when you suss them out. In any event, there’s a link within the game options to developer walkthroughs for each level, or the option to ask for a hint on the game’s Discord server, so you’re never truly stuck. All puzzle games: do this please.

Games concerning themselves with mental health issues are increasingly common, and this one doesn’t have much subtlety about it by comparison to its peers. Darkness and colour. Muddled memories. Sinister psych wards—all the classics are here, and its opaque storytelling style is a trope too. The vagueness of the narrative might be aiming for literary complexity but, well, it comes across as taking the easy route. Jumble things up with dreams and visions, leave a few questions unanswered, and hope the player does the rest.

Despite all that, I found the subject matter much more challenging than the puzzles. Without delving into the narrative specifics, The White Door is a game about feeling as bad as it’s possible to feel, and with just a few brushstrokes and some voice acting it’s unpleasantly effective in putting you in that mental space. It is also a game about feeling better, and enduring life’s colour-drained, joyless passages, emerging from the other side, and finding beauty in the smallest, simplest things. All of us can find personal relevance and significance in that, and I suppose that’s the power The White Door has.

In two hours, using art assets that while well-drawn wouldn’t look out of place on Newgrounds for their minimalism and resource economy, The White Door gets under your skin and makes you feel what it’s like to be somebody else. And it does this not with its exposition sequences or puzzles, but by making you live Robert Hill’s tightly scheduled life, toilet trips and all. It’s certainly effective at taking you to an uncomfortable place and letting you feel the truth of the sentiment that things get better.

Read our review policy

Often obtuse in its puzzle design and not that artfully told, The White Door is still effective at taking you to another place.

More Stories

Firefighting Simulator – The Squad review — Through the fire and the shame

Maid of Sker review — Death in the slow lane

PHOGS! review – It’s a dog-help-dog world out there